|

|

喬納森愛德華茲 基督教信仰從未令我快樂過!

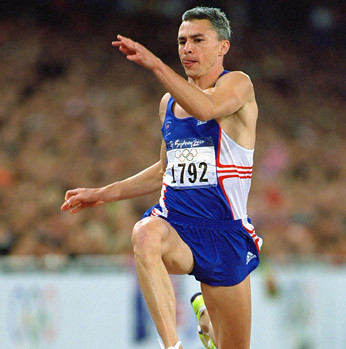

2000年9月25日下午時分, 英國運動員喬納森愛德華茲(Jonathan Edwards) 正式在澳洲雪尼獲得一面奧運三級跳遠金牌,而此時他的軍用大帆布袋內正裝著襯衫,釘子,毛巾‥ 等和一罐沙丁魚。

為何會有沙丁魚罐?這是因為魚是基督教的神話之一. 福音書寫著耶穌曾以一條魚分喂飽5000人; 是的,如果你喜歡你也可很自然的用魚這種宗教象徵物來表達你的宗教信仰。

當他剛進入奧運體育場時,他默禱:『主呀!請掌控我的命運,願我依你的意願而行!』; 幾小時後,他獲得奧運金牌,確保英國最偉大運動員之一的地位。

馬太17:20 耶穌說:「是因你們的信心小。我實在告訴你們,你們若有信心,像一粒芥菜種,就是對這座山說:你從這邊挪到那邊。他也必挪去;並且你們沒有一件不能做的事了。」

愛德華並非輕易信教,他是有根據的,重要的是他信的很澈底,打從孩提他就依照虔信雙親的安排上主日學校,他參加北德文島(North Devon )基督教青年營隊,在發誓要獻身基督時,淚流滿面充滿榮光,1987年時他來到Newcastle變成全職運動員,想靠功成名就,到非基督教區推廣基督教,他不參加 1991年東京世界錦標賽,只因與安息日衝突。

2003年他退出運動場,並豎立自已是全英最著名的重生派基督徒印象,就像使徒聖保羅所得到的光芒形象,他也成英國廣播公司BBC宗教節目讚美之音(Songs of Praise)的旗艦基督徒,他看起來與一般職業運動員的際遇大不同,或許這更加深他信仰磐石的根基。

但當他與BBC的觀眾群巡視全國的教會,愛得華遭遇到似天啟式的開悟~『基督教信仰根本是誤已誤人; 他過去的神靈顯現經驗不過是自欺欺人; 他心中的神靈感知不過是虛假的; 他接受神進入心靈中不過是立基於自我有神的假定,聖經不僅是非真實且錯誤連連,生命不僅沒有因神深受影嚮,而且可能是宇宙無意識的意外結果。』

澈底脫離福音派教會後,他實質上已是無神論者(按:有神論是指有一造物者的神),為何呢?在他於二月份脫離讚美之音( Songs of Praise)後,基督教圈已流傳他自甘墮落,企圖造謠污衊他; 但對愛德華而言,這是不可能的事。

記者現正坐在這已41歲的愛德華面前,他家位於Newcastle郡的Gosforth郊區,他可不像是亂七八糟過活的人,他帶著孩兒般的稚氣,有一頭看來精神煥發的短髮,讓我印象深刻,他似乎是盼望這冗長的會見,或許他視為一種對外界表白承擔所做所為的機會!

他說:「過去我從未有一刻懷疑過我的信仰,直到我退出運動員生涯為止,信仰是我決定當職業運動員的理由,也是我做任何決定的根源,是生活上的根基,信仰讓我的每件事看起來有意義; 在我的早期運動員生涯,禮拜天一定拒絕出賽,這不是代表犧牲比賽的機會,而是暗示運動員是很重要的,它總是意味著要讚美神!』

「但當退休後,發生一些事情讓我感到驚訝,我立刻了解體育運動對我而言,是較我的信仰來的重要!突然間,過去我認為所做的到底是最好的,都不再是真實了!」

「解開我自身的一面問題,我開始探問其他的,從此我就自已詢問不停,我的世界基礎就逐漸崩潰了; 要是你開始詢問類似我的疑問~我如何真的知道有神的存在?那你就會開始在走向不信的道路了; 我在電視上與人談論聖保羅,有專家解釋聖保羅在大馬士革的路上轉信基督教,有可能是因癲癇症病發引起的!這讓我理解教會教導我們信徒要如嬰兒般,只要信不要懷疑分析的錯誤,當你肯理性分析,就會漸漸的很難相信世上會有一位造物神!」

做為一位成功的運動家,愛得華是否曾被人如此質問過?這世界紀錄保持人是否能公正對待這質問?他說:「面對問題,當我只能選擇一項決定時,我總是排斥運動心理學,但現在我了解我所信仰的神,也只是運動心理學的一種,只是替代名稱的不同吧!」

拳王阿里曾詢問道:「當上帝阿拉站在我這邊時,我怎會失敗呢?」愛德華很了解這類信仰的潛力,正如他質問拳王阿里這回教徒哲理的合理性」

他說:「即使信仰是謊謬的,去信仰某事而非自身,也會有巨大的心理學影嚮作用!就如醫藥中的安慰劑」

宗教曾對我提供巨大的安心作用,因我認為我會成功是因神在作用下的結果~「祂愛護我、讓我獲勝、使我失敗、引領我!我在奧運帶去的沙丁魚罐就是提醒我我的信仰!」

近幾個月來的劇變並未讓愛德華情感明顯受傷!

他說:「我不會對沒有神這件事存在而不高興,我不覺得現在我的生命有大的坑洞存在,反之,我較以往更感受到我的可貴人性」; 比較過去的虔信時期,我更覺受我的真實存在,這完全有異於過去37年錯謬的我,所以外界會如此對我感到默生」

「這裏還有我與家人與朋友間的關係問題,他們許多都是基督徒,但我內心的快樂勝於過去,更滿意現在的外觀,這也許是我不必戴有色的眼鏡看這世間!」

「是否有必要脫去這破爛的外衣,進入這蔚藍自由的天空?是否無一物可得,除了藍天、無知....那又怎樣!我唯一面對的問題是哲學,如果沒有上帝,難道生命就沒意義?是否死後就結束一切?這也是存在於我腦袋內的問題,我能說的唯一肯定的事,就是如果沒能發現生命的目的,我也決不會重新擁抱基督教,我不會因某事令人難過,就認為這不是真理!」

愛得華以純理智的尺度批判基督教信仰,對許多退役的運動員造成內心的騷動,有些說他是從光明進入黑暗,也有說他是脫離黑獄來到淨土,但沒人能否認他內心誠實之旅,不是嗎!

(文於網路 來源:佛教新聞天地)

June 27, 2007

‘I have never been happier’ says the man who won gold but lost God

A giant leap of faith took Jonathan Edwards to Olympic glory in Sydney. Then he found the foundations of his life were crumbling

It is the afternoon of September 25, 2000, and Jonathan Edwards is making his way to the triple jump final at the Olympic Stadium in Sydney. In his kitbag are some shirts, spikes, towels – and a tin of sardines.

Why the sardines? They have been chosen by Edwards to symbolise the fish that Jesus used in the miracle of the feeding of the 5,000. They are, if you like, the physical manifestation of his faith in God.

As he enters the stadium, he offers a silent prayer: “I place my destiny in Your hands. Do with me as You will.” A few hours later he has captured the gold medal, securing his status as one of Britain’s greatest athletes.

“I tell you the truth, if you have faith as small as a mustard seed, you can say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there’ and it will move. Nothing will be impossible for you.”

— Matthew xvii, 20

Edwards’s faith was never an optional add-on. It has been fundamental to his identity – something that has permeated every fibre of his being – since his trips to Sunday school in the company of his devout parents; since he went to a Christian youth camp in North Devon and devoted his life to Jesus, tears streaming down his cheeks and his face glowing with divine revelation. Since he decided to risk everything to follow God’s revealed path, moving to Newcastle in 1987 to become a full-time athlete in the belief that his preordained success would enable him to evangelise to an unbelieving world; since he withdrew from the World Championships in Tokyo in 1991 because his event was scheduled for the Sabbath.

By the time Edwards retired from athletics in 2003, he had established himself as one of Britain’s most prominent born-again Christians. He soon landed the job of fronting a landmark documentary on the life of St Paul and also secured the presenting role on the BBC’s flagship religious programme, Songs of Praise. He looked to have made the transition to life after sport with a sureness of touch that eludes so many professional athletes. Perhaps this was another advantage of his bedrock faith in God.

But even as he toured the nation’s churches with his BBC crew, Edwards was confronting an apocalyptic realisation: that it was all a grand mistake; that his epiphany was nothing more than self-delusion; that his inner sense of God’s presence was fictitious; that the decisions he had taken in life were based on a false premise; that the Bible is not literal truth but literal falsehood; that life is not something imbued with meaning from on high but, possibly, a purposeless accident in an unfeeling universe.

Having left his sport as a dyed-in-the-wool evangelical, Edwards is now, to all intents and purposes, an atheist. But why? It is a question that has reverberated around the Christian community since the rumours began to circulate when Edwards resigned from Songs of Praise in February. Edwards a backslider? Impossible.

I am sitting opposite Edwards, 41, in the garden of his large home in Gosforth on the outskirts of Newcastle, but he does not resemble a man whose world has been turned upside down. His boyish face, cropped with sparkling, silver-grey strands, is alert and alive. One gets the impression that he is looking forward to the ordeal of a lengthy interview. Perhaps he regards it as a kind of confessional, an opportunity to bare all and be done.

“I never doubted my belief in God for a single moment until I retired from sport,” he says. “Faith was the reason that I decided to become a professional athlete, in the same way that it was fundamental to every decision I made. It was the foundation of my existence, the thing that made everything else make sense. It was not a sacrifice to refuse to compete on Sundays during my early career because that would imply that athletics was important in and of itself. It was not. It was always a means to an end: glorifying God.

“But when I retired, something happened that took me by complete surprise. I quickly realised that athletics was more important to my identity than I believed possible. I was the best in the world at what I did and suddenly that was not true any more. With one facet of my identity stripped away, I began to question the others and, from there, there was no stopping. The foundations of my world were slowly crumbling.”

Edwards retains the earnest intensity that was his hallmark when he gave talks and sermons at churches up and down the country. He is a serious person who regards life as a serious business, even if he is now unsure of its deeper meaning. But why did someone with such a penetrating intellect leave it so long to question the beliefs upon which he had constructed his life? “It was as if during my 20-plus-year career in athletics, I had been suspended in time,” he says.

“I was so preoccupied with training and competing that I did not have the time or emotional inclination to question my beliefs. Sport is simple, with simple goals and a simple lifestyle. I was quite happy in a world populated by my family and close friends, people who shared my belief system. Leaving that world to get involved with television and other projects gave me the freedom to question everything.”

“Where is the wise man? Where is the scholar? Where is the philosopher of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world?

— 1 Corinthians i, 20

“Once you start asking yourself questions like, ‘How do I really know there is a God?’ you are already on the path to unbelief,” Edwards says. “During my documentary on St Paul, some experts raised the possibility that his spectacular conversion on the road to Damascus might have been caused by an epileptic fit. It made me realise that I had taken things for granted that were taught to me as a child without subjecting them to any kind of analysis. When you think about it rationally, it does seem incredibly improbable that there is a God.”

Would Edwards have been as successful a sportsman had he been assailed by such doubts? It is a question that the world record-holder confronts with bracing candour. “Looking back now, I can see that my faith was not only pivotal to my decision to take up sport but also my success,” he says. “I was always dismissive of sports psychology when I was competing, but I now realise that my belief in God was sports psychology in all but name.”

Muhammad Ali once asked: “How can I lose when I have Allah on my side?” Edwards understands the potency of such beliefs, even as he questions their philosophical legitimacy.

“Believing in something beyond the self can have a hugely beneficial psychological impact, even if the belief is fallacious,” he says. “It provided a profound sense of reassurance for me because I took the view that the result was in God’s hands. He would love me, win, lose or draw. The tin of sardines I took to the Olympic final in Sydney was a tangible reminder of that.”

The upheaval of recent months has not left Edwards emotionally scarred, at least not visibly. “I am not unhappy about the fact that there might not be a God,” he says. “I don’t feel that my life has a big, gaping hole in it. In some ways I feel more human than I ever have. There is more reality in my existence than when I was full-on as a believer. It is a completely different world to the one I inhabited for 37 years, so there are feelings of unfamiliarity.

“There have also been issues to address in terms of my relationships with family and friends, many of whom are Christians. But I feel internally happier than at any time of my life, more content within my own skin. Maybe it is because I am not viewing the world through a specific set of spectacles.”

“If I should cast off this tattered coat, And go free into the mighty sky; If I should find nothing there, But a vast blue, Echoless, ignorant – What then?

— Stephen Crane, The Black Riders and Other Lines

“The only inner problem that I face now is a philosophical one,” Edwards says. “If there is no God, does that mean that life has no purpose? Does it mean that personal existence ends at death? They are thoughts that do my head in. One thing that I can say, however, is that even if I am unable to discover some fundamental purpose to life, this will not give me a reason to return to Christianity. Just because something is unpalatable does not mean that it is not true.”

His crisis of faith offers a metaphysical dimension to the inner turmoil that afflicts so many sportsmen on their retirement. Some will say he has journeyed from light into darkness, others that he has journeyed from darkness into light – but none could doubt the honesty with which he has travelled. The Eric Liddell of his generation has sacrificed his religious beliefs on the altar of intellectual honesty, a martyr of a kind.

World of his own

— A committed Christian, Edwards refused to compete on a Sunday until 1993, most notably missing the 1991 World Championships in Tokyo. “It is an outward sign that God comes first in my life,” he said at the time.

— Contested the World Championships for the first time in 1993, the first of five successive appearances, winning a medal at each one, including gold in 1995 and 2001.

— There was little hint of his 12 months to come in 1995 when, the previous year, he finished sixth at the European Championships, second at the Commonwealth Games and was ranked No 9 in the world.

— Edwards’s life changed in 1995, when he set three world and seven British records, achieving the unprecedented feat of two world records in his first two jumps of the final of the World Championships in Gothenburg. His 18.29 metres that day remains the world record. His wind-assisted 18.43, to win the European Cup in Lille, is the longest triple jump on record.

— A run of 22 consecutive victories ended when he finished second to Kenny Harrison, of the United States, at the 1996 Atlanta Olympic Games. Edwards had finished 23rd and 35th in his two previous Olympics and finished second and third at the World Championships between Atlanta and the 2000 Olympics in Sydney, where he took gold.

Words by David Powell

‘I have never been happier’ says the man who won gold but lost God

http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/sport/more_sport/athletics/article1991114.ece?Submitted=true |

|