|

|

西班牙30萬嬰遭販賣神父修女狼狽為奸

佛教新聞天地2014/07/17 01:47

英國廣播公司(BBC)紀錄片揭發,西班牙在佛朗哥統治期間,全國醫生、護士,以及天主教神父和修女狼狽為奸,組成龐大嬰兒販賣網絡,50年間偷走共30 萬名嬰兒,轉售予領養者圖利。惡行令無數受害家庭跟親生骨肉分離,被販賣兒童今天長大成人,紛紛要求政府正式調查,但與親生父母團圓的機會十分渺茫。

《每日郵報》報導,佛朗哥於1939年掌權,他向對其政權有威脅的家庭落手,偷走他們的嬰兒。但他於1975年去世後,在全國擁有極大影響力的天主教會仍 繼續販賣活動,操控醫生護士從事惡行。西班牙要到1987年才從醫院手中規管嬰孩領養,販賣活動維持長達50年。專家相信,從1960年至1989年期 間,有15%的領養案件屬於非法買賣。BBC紀錄片《世界:西班牙被盜嬰兒》(This World: Spain's Stolen Babies)詳細記錄事件。

謊稱夭折 偽造出生證明

受害人不少是未婚懷孕少女,醫院會向她們謊稱嬰兒夭折,並阻止她們看嬰孩「遺體」和「埋葬」過程。醫院其後把嬰兒賣給無子女的夫婦。多數領養者對實情毫不知情,以為領養的嬰兒都是遭人拋棄。醫院再偽造嬰兒的出生證明書,寫上養父母的名字。

事件沉寂多年,最終由當年被領養的莫雷諾及巴羅索揭發。莫雷諾「父親」臨死時承認,當年跟巴羅索父母一同用巨款向神父買下兩人。巴羅索指金額可比房子價格,他父母分期付款,用了10年才能還清。事件曝光後,引起全國哄動

Searching for Spain’s stolen babies

An estimated 300,000 children were taken from their mothers at birth and placed with adoptive families. The trouble is, most don’t know it. MARY VALLIS / TORONTO STAR Order this photo MARY VALLIS / TORONTO STAR Order this photo

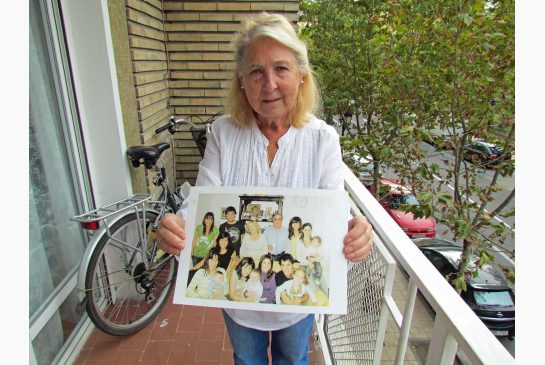

At 70, Luisa Fernanda Marin Valenzuela is surrounded by a bustling family of nine children and seven grandchildren, but she believes there is someone missing from her family portrait. Valenzuela says a tenth child, a tiny son, was stolen from her after she gave birth in 1974, although she was told the child had died. "The uncertainty of not really knowing...that really is shattering," she says.

By: Mary Vallis Toronto Star, Published on Tue Nov 08 2011

ZARAGOZA, SPAIN—In November 1974, Luisa Fernanda Marin Valenzuela stood in a doorway at a medical clinic. A male nurse held one arm and a nun held the other. About 36 hours earlier, she had given birth to a baby boy. Far across the room, she could see a tiny baby’s naked body on a table. They told her it was her dead son.

She wanted to get closer, to hold him, to cover his cold skin, perhaps even whisper his chosen name, Antonio. But the nun and nurse refused to let Luisa, who was wracked with grief, move closer to the child. Instead, they led her away.

“She’s going to faint, she’s going to faint,” she remembers them saying as they pulled her back. “Take her home.”

It was the first and only time Luisa saw the baby they said was her son. Thirty-seven years later, she is convinced it wasn’t him. She, like hundreds of other mothers across Spain, believes her child was stolen.

What began as a trickle of revelation about General Francisco Franco’s ideological cleansing by taking children from their parents is now a fully engaged scandal in a country wracked by debt, unemployment and civil unrest. As many as 300,000 babies, Spaniards have been told, were wrested from their mothers between 1960 and 1989 by a network of doctors, midwives, priests and nuns who then sold them to infertile couples for huge sums.

The scandal emerged four years ago, when a dying father revealed to his son, Juan Luis Moreno, that he and a childhood friend, Antonio Barroso, had, in fact, been bought from a priest and a nun for about 200,000 pesetas each in 1969, money that could have bought a small flat. Pesetas were the Spanish currency until 2002.

Nobody knows for sure how many children — and parents — are living false lives. Nearly 1,000 lawsuits have been filed in courts ill-prepared to handle them. And with the scandal has come a stream of shocking details — tiny corpses kept in freezers as decoys to show grieving parents; nuns with million-dollar real estate holdings and caskets exhumed after decades found empty.

Plunged into uncertainty, questioning mothers and children are paying hundreds of euros for their own DNA testing; the results are ripping their families apart.

So far, six stolen children have been reunited with their biological families, providing many with hope that their long lost children are alive. It is only now that many have even considered the prospect that they may have been told something other than the truth, including Luisa.

She is 70 now, a mother of nine and grandmother of seven. Remembering those moments long ago, she wipes tears from her eyes again and again.

“You can overcome death. It takes a long time, it’s very painful, but you can overcome it,” she says. “But the uncertainty of not really knowing . . . that really is shattering.”

The stories of the many grieving mothers bear striking similarities. Many were anesthetized during labour. When they awoke, they were told their babies had died. Many never held their babies, or even saw them.

Stolen babies have a long history in Spain. During the reign of General Francisco Franco (1936-1975) tens of thousands of children were stolen, beginning in the 1930s. Children were taken from left-leaning parents and placed with more politically suitable families to protect their “moral education.” Others were taken from single mothers and given to “proper” Catholic homes.

“In Spain, the precedent was really set during the civil war,” said Antonio Lafarga Sábado, Luisa’s husband. “But the weird thing is, it just carried on. It didn’t stop.”

As Spain became a democracy, those with access to newborns appear to have carried on the tradition because the trade was so lucrative.

The story of Moreno and Barroso, who grew up in Vilanova i la Geltrú, a seaside town about 50 kilometres south of Barcelona, started the avalanche of current courts cases. After the elder Moreno’s deathbed confession in 2007, so much made sense. Moreno understood why he towered over his diminutive father and looked nothing like his mother.

The childhood taunts Barroso endured in the schoolyard — children claiming he wasn’t really his mother’s child — came rushing back. She’d always insisted their claims weren’t true, and even told him vivid stories about her labour pains.

When Barroso was in his teens, he went to a local registry office and pulled a copy of his birth certificate, which listed the name of his adoptive mother; the staff insisted there could be no mistake. He put it out of his mind until the confession came; by that time he was 38.

“I’d always suspected it,” Barroso, 42, says, fiddling with a copy of his inaccurate birth certificate. “When I was young, there was no real way to confirm it, but now, with DNA tests available, the whole thing becomes so much clearer that all my life has been a lie.

“I’ve been lied to and I’ve been fooled.”

The men took DNA tests that confirmed the dying man’s story. Barroso has since abandoned his career in commercial real estate. He has filed lawsuits at every level in the Spanish court system and founded the National Association for Victims of Irregular Adoptions (Anadir).

More than 1,800 people are members of the group, which maintains a DNA database for parents who fear their babies were stolen, and people who suspect they were trafficked.

About 930 lawsuits have been filed. The majority have been rejected; judges cite statutes of limitations, a lack of evidence and the fact that key witnesses are dead.

Spain’s laws have also made investigation difficult. Babies that die within 24 hours are considered aborted fetuses and are often buried together in their own section of cemeteries — making it hard to extract DNA evidence, according to Lorenza Álvarez, who is coordinating the stolen baby cases for Spain’s attorney general’s office.

Still, a small but growing number of cases are proceeding. Tiny graves are being exhumed throughout Spain. Some are empty; others contain only wads of medical gauze or bandages, not tiny bones.

In two caskets, investigators found remains that have no genetic link to their supposed parents — evidence, Barroso reasons, that the babies were swapped with those of couples who had stillborns.

One woman has told reporters that in 1969, a priest encouraged her to fake a pregnancy until a child became available for purchase. And a man who drove babies’ caskets to a cemetery in southern Spain says at least 20 of the boxes were far too light to hold children’s remains — or, for that matter, to hold anything at all.

Spanish journalists who investigated a clinic in Madrid that is listed in many legal claims found a baby’s corpse in its freezer. There have been suggestions it was kept there to show parents who demanded proof their children had died.

The scope is staggering. Barroso feels he is single-handedly leading the charge for justice. He is tired; dark circles hang beneath his eyes as he explains his frustration.

“It’s shameful that Spain, which likes to presume to be a law-abiding society, one that wants to give the impression of being a democratic, modern society, should have had this going on,” Barroso said. “You basically have to laugh so as not to break out crying.”

When Barroso learned he had been bought, his mother was ill. He surreptitiously swabbed her cheek for DNA tests that proved she was not his biological parent. She eventually confessed that a nun she had befriended did her a favour.

He and Moreno followed the trail to another nun, now 85, and in hospital. The men have visited her several times — hoping she will reveal the names of their real mothers. But she has revealed nothing.

“She remained absolutely unmoved,” Moreno says. “She said her conscience was at peace. She helped mothers in a disgraceful situation. She had nothing but peaceful thoughts.”

The nun has not been charged with any crime. The Roman Catholic Church has not commented.

Barroso and Moreno have learned that she owns seven properties, estimating her worth at one million euros (nearly $1.4 million Canadian). One of the properties was inherited and another was donated, but the remaining five appear to be outright purchases.

“How is it possible that a nun with espoused vows of chastity, poverty and obedience should be worth so much money? How has she accrued so much property?” Moreno asks.

Moreno and Barroso have presented their lawsuits at all levels in the Spanish court system, but they have been consistently rejected.

In January, Anadir presented 261 cases to Spain’s attorney general and held a rally in an attempt to draw public attention. It was then that the government took the issue seriously and began referring cases to provincial judges.

The prosecutor’s office has since authorized exhumations and some cases are proceeding, Álvarez said.

Luisa’s case is not among them. Her lawsuit was dismissed in late September because the midwife and doctor are both dead.

Sitting in her living room, surrounded by family photographs, she fingers a photocopy of the burial record from the cemetery that contains her family niche.

At the clinic, she was told her newborn had died around 11 a.m. on Nov. 24, 1974, about 36 hours after his birth. She says she refused to leave the clinic until she saw his body.

But the burial record shows that by the time staff showed her the baby’s body, he would have already been buried.

What’s more, her husband Antonio clearly remembers picking up his son’s remains and taking them to the cemetery the following day, on Nov. 25. But that date does not appear in any of the records.

The couple, who were then in their 30s, trusted their doctor and the clinic. They had already delivered two healthy girls with his help.

“All my children have been born perfectly healthy,” Luisa says.

“The likelihood here was that this boy was going to be a very healthy little boy. That’s why I think it happened to us.”

She returned to the same doctor for four more births. Strangely, he waived his fees for one birth. Did he feel guilty, they wonder.

Their flat is always bustling with activity. Down the hall, some of their daughters and grandchildren have gathered for a family lunch.

One of their granddaughters scampers down the hall for a kiss on her way to school. Luisa gives her a tight hug.

“Other people say, ‘Listen, you’ve got nine and they’re all extremely healthy,’” Luisa says. “But there’s one that’s missing.”

“There is one missing,” echoes her husband. |

|