本帖最後由 誠惶誠恐 於 2022/7/22 10:50 編輯

【注:以下一文用的記譜法,馬(騎士Knight)的代號是「S」(騎士德文Springer的第一個字母)而非「N」,這是棋題界的習慣】

What is a Chess Problem?

by Peter Wong

The best games of chess are considered beautiful. They are admired, and replayed around the world by enthusiasts for that reason, apart from the practical use of studying such games. Yet when we play a game, the only real consideration is how to win it, never mind whether the method of winning is attractive or not. What if we devise a position specifically to demonstrate a beautiful or artistic chess idea? That, in fact, is what occurs in the composition of a chess problem. When you solve such a problem, its composer’s aesthetic intent is revealed in the play of the solution.

So chess problems – also known as chess compositions – are enjoyed on two levels. On a basic level, they work as challenging puzzles. You are given a position and an accompanying task, such as “White to play and mate in two moves”, that must be fulfilled. On a higher level, problems are aesthetic works designed to show an interesting theme – the composition’s main idea. How exactly are themes artistic? It varies, but important factors include subtlety, elegance, economy, paradox, and unity of play. The latter concept of unity is especially noteworthy; most good problems have multiple variations that are related to each other in some way, to create a harmonious impression.

Chess problems come in a variety of genres, the most common of which is the directmate. In this type of problem, White plays first and forces mate in the specified number of moves, against any Black defence. Only one of White’s first moves is able to achieve this, and the solver’s task is to discover this unique move, called the key. If another move, unintended by the composer, solves the problem too, that alternative move is called a cook, and the problem becomes unsound. Such faulty problems, however, are rarely seen nowadays (especially in directmates) because of the practice of computer-testing, which ensures that cooks are eliminated.

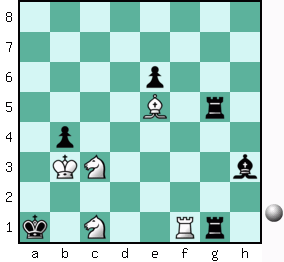

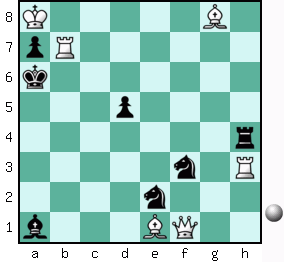

1. Otto Wurzburg

American Chess Bulletin 1942

3rd Hon. Mention

Mate in 2

Let us consider our first example, 1, a two-mover. The problem’s stipulation or task is given next to the diagram as “Mate in 2”, indicating it’s a directmate and White must mate by the second move. The solution begins with 1.Kc2! – the '!' signifies the key – after which the threat is 2.Sb3 mate. Black can parry this threat with various defences, but these moves enable White to mate in other ways. For example, 1…bxc3 2.Bxc3 – the two moves here, Black’s defence and White’s correct response, constitute a variation. The main variations of this problem are 1…Bf5+ 2.Se4, 1…R1g2+ 2.S1e2,and 1…R5g2+ 2.S3e2. These lines represent the thematic play because they share a number of elements: Black checks, but unguards a white piece (rook or bishop) that’s training on the black king, allowing White to answer the check by interposing a knight, and discover mate at the same time. Such a tactic, in which White stops a check by interposition, and gives check as well with the same move, is known as a cross-check, and its recurring use is the theme of this problem.

Various conventions apply to key-moves in directmates, and knowing them will assist you when solving this type of problem. The desired feature of subtlety means that keys are very unlikely to be checks. Keys that capture a piece are almost unheard of, for the same reason, though the capture of a pawn is acceptable. In contrast to obviously aggressive keys that are frown upon, keys that apparently weaken White or strengthen Black are viewed as good in the artistic sense. Though not all directmates are successful in incorporating them, you should keep in mind the possibility of such paradoxical keys. A perfect illustration is 1, which has an excellent key because it exposes the white king to numerous checks.

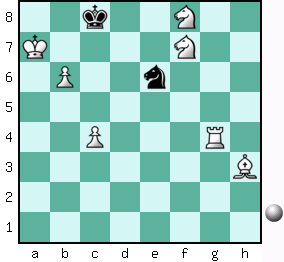

2. William Shinkman

The Problemist 1944

Mate in 2

Another major consideration when analysing a problem is whether the key creates a threat or sets up a block position. The former is already exemplified by 1, a threat-problem. In a block-problem, the key carries no threat but is a waiting move that puts Black in zugzwang. In such a position, every possible move by Black entails a weakness, which is exploited by White due to Black’s compulsion to move. Problem 2 is an example. Its key 1.c5! doesn’t threaten an immediate mate, but all moves by the black knight commit some kind of error that allows a mating reply. The variations 1…Sd4 2.Rxd4, 1…Sf4 2.Rxf4, 1…Sg5 2.Rxg5, and 1…Sg7 2.Sxg7 are similar – White discovers check and captures the knight to stop it from interfering with the bishop mate. 1…Sxc5 2.Rc4 and 1…Sxf8 2.Rg8 see the white rook pinning the knight, to prevent its return to e6. In the remaining two lines, 1…Sc7 2.b7 and 1…Sd8 2.Sd6, the errors committed by the knight are called self-blocks: a black piece obstructs a square next to the black king, freeing a white piece that was guarding it to give mate. When a black knight makes its maximum number of eight moves in a problem and induces eight different white responses, as here, the knight-wheel theme is produced.

Looking at the problems in this article, you may be struck by how the positions seem “artificial” and far removed from an actual game of chess. That only highlights how problem composition is a field distinct from the competitive game and also from game-position exercises. Chess problems are constructed in accordance with their own principles. A particularly important one of such principles is economy of force, which holds that for any given idea shown in a problem, the number of pieces used should be minimised, and that every piece should serve to bring about that idea or to ensure soundness. That the resulting problem positions do not resemble game situations is regarded as irrelevant. Nevertheless, another convention of problems links them directly to the game. Problem positions are required to be legal, i.e. they could have arisen from the opening array, however unlikely the players’ moves may have been in reaching these positions.

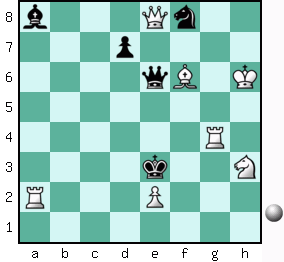

3. Charles Ouellet

The Problemist 1987

Mate in 2

A pawn on its starting rank has the potential to make four different moves – two forward steps, and two captures. If a white pawn plays each of these four moves in turn during the course of a problem’s solution, the Albino theme is shown. Problem 3, using only eight pieces, is a very economical demonstration. It is solved by a waiting move, 1.Rbb5!, after which the black rook has to release the white pawn. 1…Rb3 2.cxb3, 1…Rd3 2.cxd3, 1…Rxc5 2.c4,and 1…Rc4 (or to e3, etc.) 2.c3. There is also by-play, i.e. non-thematic or secondary variation(s): 1…Rxc2+ 2.Bxc2.

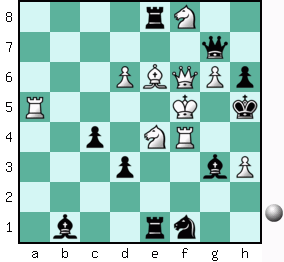

4. Alain White (version by R. Cabral)

Good Companions 1918

1st Prize

Mate in 2

Problem 4 has rich play involving pins and unpins. The white queen has the black queen pinned, and the latter in turn is pinning the white bishop, which could otherwise mate on d4 or g5. The key is 1.Qe7!, threatening 2.Qc5. Each move by the black queen defeats the threat, but also unpins the white bishop, hence 1…Qxe7 2.Bd4 and 1…Qe5 2.Bg5. After 1…Qe4, however, neither bishop mate works because the black queen has shut off the white rook’s guard of d4. But this defence permits 2.Rg3, because the pinned queen has also cut off the black bishop’s access to f3. Two further thematic variations are 1…d6 2.Qa7 and 1…d5 2.Qa3. In each case the black pawn interferes with the black queen’s control of a defensive line, enabling the white queen to unpin its counterpart with impunity in the mate.

5. Godfrey Heathcote

Norwich Mercury 1907

1st Prize

Mate in 2

Problem 5 is famous for its brilliant key that self-pins multiple white pieces simultaneously. After 1.Ke5!, the four previously mobile pieces next to the white king are all pinned by Black. The threat of 2.Kd4 induces Black to unpin these white pieces, which are then free to deliver mate; thus four matching variations are created, 1…Ra8 (or to b8, etc.) 2.Bg4, 1…Qa7 (or to b7, etc.) 2.Qf5, 1…Bf2 2.Rf5, and 1…Se3 2.Sxg3. The key also allows Black to give three more checks by capturing the pinned pieces, in addition to 1…Qxf6+, and in all cases the white king recaptures to give a discovered mate, 1…Rxe6+ 2.Kxe6, 1…Bxf4+ 2.Kxf4, 1…Rxe4+ 2.Kxe4, and 1…Qxf6+ 2.Kxf6. Also, 1…Qxg6 2.Qxg6, 1…Bh4 2.Rxh4.

6. Lev Loshinsky

The Problemist 1930

Mate in 2

Problem 6 is for you to solve. The thematic play involves self-interference, when a black piece cuts off the line controlled by another black piece.

Problem 6 solution (To display, hold down your mouse button and select the text below.)

>1.Qf2! (threat: 2.Qxa7). Black has five unified defences that occur on one square, d4. In each case the black piece interferes with a defensive line controlled by the rook on h4 or the bishop on a1. 1…d4 2.Bc4, 1…Rd4 2.Rh6, 1…Bd4 2.Qxe2, 1…Sed4 2.Qa2, and 1…Sfd4 2.Ra3. |